American businesses are employing more people than ever, the stock market has soared – even with the ten per cent correction – and consumer optimism is growing. Given this spirit, it remains a puzzle as to why productivity is lagging behind in the United States, and why are wages still stagnant. It has been 10 years since the world economy managed to limp to safety after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Most of the damage was averted thanks mainly to Quantitative Easing and low-interest rates. So given the improving economic environment, why have the vital stats of the economy lagged behind?

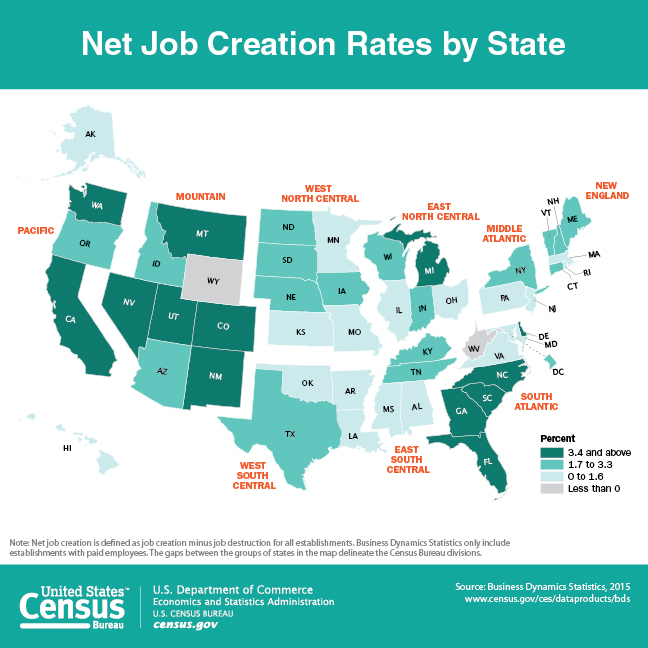

Some economists say, at least in principle, the roots lie in a steady decline in new business formations; namely startups. In 2015, the US Census Bureau listed 414,000 firms under one year old, a staggering amount to visualise, but it pales in comparison to 558,000 formations in 2006, just a few years before the GFC. The BLS even confirms the trend with the number of company births and deaths falling in unison from as early as 1998.

The UK has seen a sharper upward trend the Federation for Small Businesses having reported that since 2000 the overall business population grew by a massive 64 per cent. Even with the onset of Brexit – with its predicted economic shock – still appears to be an attractive place to do business, at least for the foreseeable future.

To make matters somewhat more embarrassing for Trump, the world’s second-largest economy does not seem to be in the same boat. China’s President, Li Keqiang, boasted at the 12th National People’s Conference that it was producing 12,000 new businesses per day, or 4.3 million a year. China’s pro-business stance, through subsidizing business and providing generous funds through state-owned financial vehicles, is working. For how long China’s strategy will work is up for debate, as the easy money turning the wheel of startups can rapidly transform into a state-sponsored bubble. Even with that in mind, the US needs to recapture the growth and ambition of the past to propel it back to being a leading innovator that it all know it to be.

Probable causes

Some speculative thinking is needed to imagine how the US has fallen in world rankings for business development. Some of America’s greatest entrepreneurs and job creators were all relatively young and enthusiastic individuals. The well-recited catalog of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Jerry Yang – who all came from modest families – are the poster boys of a vibrant and mainly young startup community. They all battled the odds to create a space for themselves and ultimately became household names. Steve, Bill, and Jerry were all in the youth when they ventured into the tech business.

Sadly, today’s youth in most Western developed nations are forever saddled with enormous students loans and debt. Compared to those attending University in 1980, students today are expected to hand over nearly five times more for a similar education. Many graduates today see themselves as part of the Lost Generation who have missed the rising tide of the economy to best realise their dreams.

STEM holders and H1B Visas

Many argue that non-marketable degree holders are distorting the employment market with their apparent unemployability. But even those with much-coveted STEM degrees are battling to compete with H1B Visa holders, who are brought in by large (usually tech) firms. While firms should be encouraged to find qualified labour to plug gaps in their workforce, many H1B Visa holders are often brought in at a lower salary than their US counterparts. Salaries for US STEM workers would need to lower their own salary expectations now that a pool of cheaper labour is the in the market. Since H1B workers are unable to negotiate for higher salaries – as they would be replaced with another H1B holder to replace them – it, therefore, makes labour arbitrage meaningless. Given this scenario, does this make globalisation at odds with the needs of these workers? With the sudden popularity of President Trump, mainly from disenfranchised workers, it does appear so. Solutions to this particular quandary are not forthcoming, at least for the moment.

The Gini is out of the bottle

Young entrepreneurs could also be hampered, before they set forth on their journey, by the ever-increasing wealth inequality. The Gini Coefficient, which is a measure of household income and its deviation from perfectly equal distribution, has indicated since 1980 to be rising. In its simplest sense the rich are really getting much richer. Along with the recent Trump Tax Cut, large corporate accounts are sloshing with finds. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway benefitted from a near $30 billion tax cut (Annual Report, Page 4). None of this can assist the young, underfunded and highly ambitious to build the next generation of startups that change the way with live and work. If Americans want to witness a nation built on meritocracy and ambition, then solving the way young entrepreneurs are financed and mentored needs to change dramatically.

Vying for attention

According to Credit Suisse and their report on the Shrinking Universe of Stocks has shown that the number of companies listed on the stock market has fallen. Starting from 1976 there were 5000 firms listed, with its absolute peak in 1996 when just over 7000 public companies in the US. Sadly, in 2016 this is now close to 3000 and has remained close to this level for the last decade. We can say for certain that there is a larger structural imbalance that is failing to be addressed and making America lose its competitive edge. The report also points out that the number of new listings is at a smaller percentage than at any other time in history, arguably making the private section the least vibrant since the Dotcom Bubble.

The most intriguing part of this analysis is how and why companies were delisted from the exchange in the first place. In normal circumstances firms which are contracting, bought out through a merger or acquisition, or collapse through bankruptcy are often removed from the exchange listings. This report analysed all known delistings and found that since 1996 the number of buyouts were on the rise and still growing. The report best highlights the issue in the following manner:

Given this outcome, it now means that becoming an innovator or market disruptor is no longer the priority of listed firms. Considering; smaller firms are now a smaller population of the market, are vastly underfunded compared to their competitors at any time in history, and are running on a finite cash pile that is being used furiously, the only sensible business conclusion is to sell up. This culture shift to companies striving to simply be a big enough product to complement a conglomerate’s portfolio is a disturbing trend. Companies may no longer compete to be the best or lower prices for consumers but to just further entrench the positions of market leaders.

To illustrate this point. Not long ago Google turned itself into Alphabet, a company of companies where Google is just one in its portfolio. But in a hypothetical sense it is a company on a mission to find the next 25 “Googles”. A product that instantly dominates the market while becoming a virtual printing press; producing billions. The scary part of this hypothesis is that the company is within reach of this goal. The firm’s founders were winners of the tech lottery with its search algorithm, and so with revenues in the billions they could easily buy the next emerging technology. Firms can be bought in the single-digit millions (or billions) while not even denting their multi-billion dollar profit margins. Have startups become lottery tickets for tech behemoths, probably. Let us hope that the sustainability of such a paradigm is closer to its end than the beginning.

Leave a Reply